1995

May 22 1995 to 1996

Abbey Road Studio Two/Penthouse Mixing Suite. Mixing/Editing (precise mixing details

unknown) : (all tracks that appear on The Beatles Anthology Vol 1-3 releases, bonus tracks on Free As A Bird single releases and Real Love single releases).

P: George Martin. E: Geoff

Emerick.

According to an excellent and lengthy article in L.R.E King's

book Fixing A Hole, the first time anyone at EMI

officially went looking through the archives for unreleased Beatles

material was in 1976, when the Beatles contract with them

legally expired.

At irregular intervals between then and 1985, EMI executives

and staff, including Geoff Emerick, worked on mixing and

compiling a single album of previously unreleased material eventually called

Sessions. Although the album made it as far as the

test pressing stage (and was subsequently bootlegged), the whole project was

finally abandoned (mainly due to the objections of George,

Paul and Ringo, who were apparently never

consulted about the album) and the EMI tapes were left to gather dust for

another decade.

Eventually, in 1995, immediately after the completion of the

Live At The BBC album, the remaining Beatles

and George Martin began compiling and mixing unreleased

Beatles material for the forthcoming

Anthology series of archive CDs.

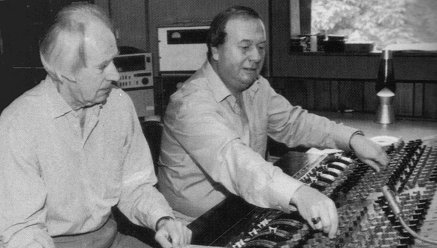

George Martin & Geoff Emerick

George Martin: I am trying to tell the story of the

Beatles lives in music, from the moment they met to the

moment they split up in 1970. I have listened to everything we ever recorded

together. Every take of every song, every track of every take, virtually

everything that was ever committed to tape and labelled 'Beatles'.

I've heard about 600 separate items in all. I didn't start any serious listening

until early this year, when I got Paul, George

and Ringo to come in occasionally and listen with me (the Beatles began attending these sessions on 31st March 1995).

The material guarded at Abbey Road Studios was largely in excellent

condition. In fact in 1988, Abbey Road engineer Allan Rouse was given the mammoth task of copying all of the Beatles' analogue recordings onto digital as a safety precaution. As a result, Rouse holds the unique distinction of being the only person to have heard literally every surviving Beatles tape stored at Abbey Road (historian Mark Lewisohn comes close, but even he didn't have the time to listen to everything when he spent several months compiling his stunning Complete Beatles Recording Sessions guide). Allan Rouse quickly joined the Anthology project, serving as co-ordinator and George Martin's assistant.

George Martin: They really know how to look after their

tapes. Those that they have kept, that is, because they destroyed an awful lot

of the early ones. In fact, there are few tapes left from the early 1962-63

sessions. A lot of the material that has come to light from that period has been

in the from of laquers and acetate discs. Occasionally, some quarter inch tapes

have emerged, but no masters as such. We only managed to get hold of two tracks

from the very first session the boys did in June 1962, and I happened to have

one of them. My wife found it and it transpired that no one else had it. That

was Love Me Do, the other being Besame Mucho, both with

Pete Best on drums. There are other things which I thought had

gone forever, such as an early version of Please Please Me which we

recorded in September 1962. It doesn't have the harmonica on it but it's very

interesting, with a totally different drum sound.

Clockwise from bottom left:

George Martin, his assistant and co-ordinator Allan Rouse,

Paul Hicks and Geoff Emerick

Archived Beatle tapes are never allowed outside the Abbey

Road building. As a result, all the listening and subsequent mixing sessions

were held at the studio's penthouse suite. The normally beneficial modern

technology that is plentiful at Abbey Road posed a dilemma for George

Martin.

George Martin: If I was going to remix a recording made in

the 1960s on four or even eight tracks, there would be no point in processing it

in a modern manner. What I really wanted was an old valve desk, although I knew

that it would be causing more trouble that it was worth, because if we found

something suitable it would inevitably be unreliable. To our great fortune we

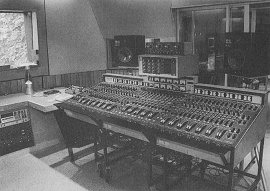

discovered this early 1970s console and there is no question that it does affect

the sound.

Geoff Emerick: We discovered that Jeff Jarrett, who used to be an engineer at Abbey Road an actually did some work with the Beatles, had bought one of these old consoles when it was sold off in 1987. It was one of EMI's first transistorised TG Series desks, and although this particular one had been taken out of the studio, and adapted for use by Mobile Recording Unit, it was basically the same desk that I'd used for the Abbey Road album

US$788,000 worth of modern equipment was replaced with this 1970s mixing

board for a string of mixing sessions which began in earnest at Abbey Road on

22nd May 1995 (precise mixing details and dates are unknown, although the old mixing console was installed in the Penthouse Studio for around sixteen weeks in total that stretched into 1996).

The old mixing desk back in place

George Martin: In the spirit of the exercise I couldn't

justify using modern effects processors like digital reverb, or even echo

plates, which didn't exist in the 60s. The only way we could achieve echo was by

using either a chamber or tape delay. Unfortunately, neither of the two echo

chambers that we used at Abbey Road was available. One has an enormous

electrical plant in it, emitting terrible humming noises. Eventually they were

able to dig out and refurbish the second chamber to make it work for us the way

it used to, even to the extent of putting back a lot of the old metalwork

sewage pipes, which were originally glazed and actually contributed to the

chamber's acoustic qualities.

As each item was eventually given approval by the Beatles, it was passed onto Geoff Emerick and his assistant, Paul Hicks (son of Hollies guitarist Tony Hicks) for remixing.

Geoff Emerick: I have fought very shy of being pushed into using alot of the modern devices. So many of today's digital processors are based on the sounds that we used to achieve manually, but quite honestly I don't think they sound as good. We can still get those sounds by old methods quite easily, and much quicker too. In fact, thinking about it we haven't really progressed that far, if anything it's probably the opposite. The old 4-track masters are on one inch tape, so every track is almost a quarter of an inch wide. As a result, apart from the lack of noise, the quality of the bass is outstanding, you just can't create that now. The same applies to the snare and and bass sound, they sound so natural it's uncanny.

Sources include: Allan Kozinn; The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions

- Mark Lewisohn (Hamlyn Publishing 1988); Fixing

A Hole - LRE King (Storyteller Productions

1989); Mojo Magazine Dec 95; Independent On Sunday 16th Jul 95; Q Magazine Jun

97; Abbey Road - Southall/Vince/Rouse (Omnibus Press 97); Beatles Monthly No. 235 Nov 95, No. 236 Dec 95, No. 249 Jan 97 (Beat

Publications)

Last Entry : 30th November 1994 Release

Main Contents

Next Entry : 6th & 7th February 1995 Session